Instacart: When Do Partners Become Competitors?

As a result of the pandemic and the resulting changes in consumer shopper patterns, many retailers have had to spin up new order fulfillment and delivery capabilities very quickly. Fast-moving-consumer-goods (FMCG) retailers – grocers, drug stores, and c-stores already knew that they were going to need to respond to meet consumer demands for direct-to-consumer (D2C) fulfillment sooner or later. I looked back into some of our recent benchmarks, and found this early reference in our 2018 supply chain benchmark:

“… it’s FMCG’s turn, and that they are the now most concerned about developing the new metrics required to get their hands around the cost issue:

FMCG Retailers Feeling The Heat

|

Top Operational Challenges |

GM |

FMCG |

Apparel & Brand |

Hardgoods & Other |

|

Quantifying labor & shipment costs for cross-channel fulfillment |

54% |

70% |

42% |

33% |

Source: RSR Research, December 2018

Right behind that top operational challenge <is a> speed-related problem: … when we look at these two operational challenges by retail vertical, the result reveals current market issues:

FMCG – More Heat

|

Top Operational Challenges |

GM |

FMCG |

Apparel & Brand |

Hardgoods & Other |

|

Shipping direct-to-consumer orders fast enough |

50% |

55% |

38% |

47% |

Source: RSR Research, December 2018

FMCG’s concern about being able to ship direct-to-consumer orders fast enough is a ‘now’ issue, as Tier 1 operators like Walmart, Target, and Kroger invest heavily in same-day delivery.”

But even as recently as March 2020, we reported that “<while> same day fulfillment is perceived as a real differentiator, <we> would have expected to see that most strongly in the world of fast moving consumer goods (FMCG)… in fact, only 29% of respondents cite this as a top-three issue. All other verticals feel the pressure more.”

Well… as we’ve said many times in the last year, COVID-19 has acted as an accelerator. And in this case, many FMCG retailers “solved” the accelerated demand for home deliveries via partnerships.

The biggest beneficiary in the rush has been Instacart. In fact, the company, which had been reporting a monthly loss of $25M before April 2020, saw its first profitable month at that time (+$10M), and this in turn led Founder & CEO Apoorva Mehta to say that the company had passed its 2022 goals. That probably helped the company achieve its latest round of funding ($265M) and subsequent market valuation ($39B). Instacart now partners with nearly 600 national, regional and local retailers, offering delivery and pickup services from more than 45,000 stores across the U.S. and Canada.

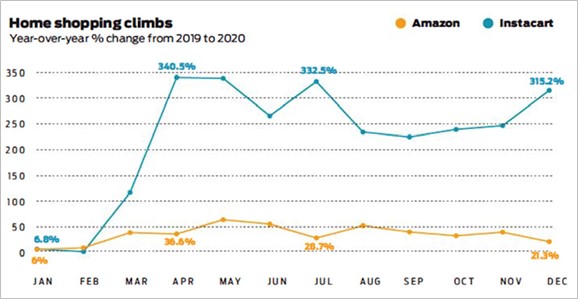

Just to show how much Instacart has benefited is plain when you look at its performance in the last year in its home market, San Francisco, compared to Amazon, here’s a chart from the SF Chronicle:

Source: San Francisco Chronicle, March 15, 2021

In all probability, many of the retailers that have partnered with Instacart could not have provided D2C delivery to consumers any other way in the year of COVID. The pandemic caught them in a real bind, and Instacart’s platform got them out of it in a friendly (albeit expensive) way. The question now is, can retailers take D2C home deliveries on themselves and begin addressing the cost challenges associated with such a program? And a related question is, why shouldn’t Instacart become its own grocer?

First things first. Big grocers can and probably should make D2C operations more efficient, and that probably means taking it in-house. But that would mean some important capabilities have to be developed. First, there has to be a better way of picking the orders than what happens now with Instacart “shoppers” who clog the aisles at retail stores. And Instacart isn’t standing still either! The company upped the ante when it recently ordered large-scale automated equipment to be able to fulfill orders for their retailer partners from Instacart fulfillment locations.

One potential solution for over-stored grocers is to establish “dark store” fulfillment locations. Another is to mimic what Instacart has done – use contracted shoppers/drivers to pick orders in the stores and deliver them. In either case, retailers would be required to develop the ability to manage a network of vehicles. That might look something like Lyft. Website www.techboomers.com describes Lyft this way:

“Lyft is an independent taxi service that hires people to use their own vehicles to drive passengers around. The passengers use an app to request a ride, and can be picked up and dropped off anywhere. Payments are made through the app, so there is no need to find cash to pay at the end of the ride.”

In a grocer’s case, the “passenger” is the customer, and the “ride” is the order. The retailers would need to ability to track its network of drivers, match them to orders based on several factors including the driver location and availability, proximity to a fulfillment location, distance to the drop-off location, and per-order requirements (such as time-to-deliver, etc.). Once retailers have control of the data, they can start optimizing the fulfillment and delivery network.

As you might expect, technology providers that enable those kinds of capabilities exist today. It comes down to being able to capture the location data generated by mobile devices or vehicles and using that data to manage a fulfillment and delivery network.

But can everyone “play”? Perhaps for a local retailer, a full-featured service like Instacart is the only option. But I wonder why big retailers like Costco, Albertsons, Kroger, and Walmart haven’t taken up the challenge yet. Maybe the need came up too quickly, or perhaps there were so many other top priorities that have taken priority (for example, omnichannel order management, which is an absolute requirement in such a scenario).

But if retailers are waiting for consumer to come flooding back to the stores once they get their vaccines, they might want to think again!

The Other Question: When Do Partners Become Competitors?

The other nagging question that has resulted from Instacart’s successes is, will it decide to become a next-gen grocer? This is not a new question, but it’s gaining a lot of attention nowadays. For its part, Instacart is sticking with its non-competition stance, but voices from the investment community are suggesting that the company will have no choice in order to maintain its market valuation.

Consumer switching costs for grocery are notoriously low, and that gives rise to these kinds of conversations. On the flip side of the argument, the level of experience and expertise to be a successful grocer is not to be dismissed. But it’s also true that grocers have to do a much better job of “upping the value” of their relationships with consumers – and that ultimately leads to a discussion about if and how retailers are moving towards more customer-centric value propositions. That’s a discussion for another time, but that’s how the potential threat of disintermediation by the likes of Instacart should be addressed.

Simply put, to stay viable, grocers must become indispensable to consumers’ lifestyles. Then how the groceries get delivered and even how much that costs won’t be such big issues.