The UK’s Debenhams: A Cautionary Tale

Last week, UK retailer Debenhams, at one time England’s largest department store chain, threw in the towel after having twice gone into administration (or “bankruptcy protection”, as it is called in the US), and started liquidation proceedings. While at this writing the company is in talks with a potential last-minute buyer, there’s a very real chance the 242-year-old retailer will close its doors forever at the end of the year, costing 12,000 employees their jobs, and dealing another blow to the UK’s High Street retailers.

This is a now familiar story, and it’s sad to hear, but it’s also a cautionary tale for other “legacy” retailers that are still trying to finesse their way through the transformation triggered by consumers’ digitally enabled shopping behaviors. Here’s a quick synopsis of the company’s recent history:

- In 2003, the company had an outstanding debt of £100 Million, and it was acquired by a private equity consortium for £600 Million;

- The PE owners installed a leadership team that engaged in aggressive cost cutting, selling off poor performing locations and executing sale/lease back transactions to extract money from its real estate holdings, and engaging in spiraling discounting programs to clear inventory;

- The company canceled a large (late and over-budget) business re-engineering project and ERP implementation;

- Carrying a debt of £1 Billion by 2006, the company was re-floated on the stock market (delivering a big payout to the PE ownership group), but subsequent earnings were not enough to cover all the debt the company had taken on;

- The Great Recession hit in 2008. Simultaneously, consumers began using new smart mobile technologies to inform their purchasing decisions, triggering what we now know as the “omnichannel revolution”;

- Debenhams operations remained channel specific, and because of the cancelled re-engineering effort earlier in the decade it relied on its legacy processes and systems to perform new tasks associated with omnichannel shopping and fulfillment – which had become popular in the UK;

- In the meantime, the company bought several brands that ran concessions in its stores, making those brands exclusively available at Debenhams. The company also acquired a retailer in Denmark. Finally, it moved its headquarters, and embarked on several store remodels. In other words, it took on more debt;

- Throughout the last decade, the company continued to struggle;

- Fast forward to 2019, the company went into administration. In April 2020 the company again sought bankruptcy protection, closing many stores;

- In December, talks with a potential buyer, Arcadia Group, collapsed when Arcadia went into administration (that’s another story!). Debenhams announced liquidation proceedings.

I wanted to understand a little of the inside story, and so reached out to John Andrews, the Founder & Chair at IORMA – The Global Consumer Commerce Centre. I’ve known John for over a decade, and have valued his insights into the UK retail environment. He in turn connected me with John Scott, the founder and CEO of Liminal Retail, an independent consumer consultancy. John worked at Debenhams from 2010-2017 as its director of international business development. We spoke last week about the news, and what it means to struggling High Street retailers.

I was particularly interested to understand if and how Debenhams had come out of the Recession in embracing new consumers shopping behaviors, my going-in assumption being that like so many other companies, the retailer might have missed the significance of the new behaviors. John Scott explained:

“Debenhams were early adopters in terms of recognizing the importance of having a website. The issue they had was how they should invest their money. Let’s take a step back; when the business was taken into private ownership, they were about 2/3 the way through a transformation project which, like these transformation projects tend to do, went way over budget and had taken up half the resources of the business, because it had very old merchandise systems. The first thing the new ownership did was to stop the program, essentially to scrap it and leave the company with the legacy merchandise system that it had. What that meant was that anything we needed to do had to be bolted on to the old system. As part of the transformation project, they’d let go of most of the people who understood how the legacy system worked – because they didn’t need them anymore! So, they had to bring some of them back at exorbitant fees to keep it going for a period of years. Debenham’s still pretty much relies on it.

“So, they were trying to put a front-end digital platform and integrate it to something which really wasn’t geared up to deal with that, so they were throwing a lot of money trying to do the supply chain redevelopment for E-comm. They spend quite a lot of money early on – probably too early and too much money – and they got their fingers burned. For example, about 8 years ago they tried to go into Germany and got a consultancy to tell them how to do it, and it was a complete disaster. In the end, the E-Comm director explained to me that they had ‘put a Ferrari engine in a Ford’. It essentially didn’t give the company what it needed.”

There’s a lot to unpack here.

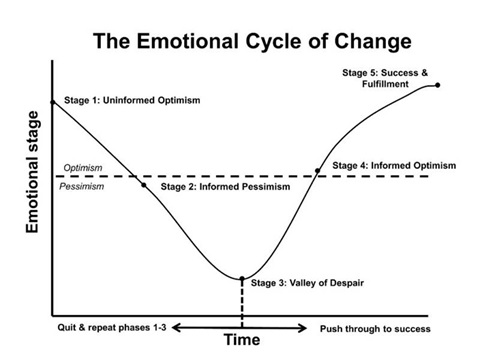

For one thing, I am reminded of the top inhibitors that RSR’s research keeps revealing about any transformative process: old systems, old attitudes, and a belief that events can somehow be controlled or at least that some of the effects of those changes can be negotiated away. Those familiar with the “change cycle” know that regardless of the nature of any change, individuals, organizations, and even societies go through the process illustrated here:

Debenhams was clearly stuck in phases 1-3 and couldn’t break out of the spiral. I remember thinking about this phenomenon a few years back when we interviewed the Sears E-commerce team. It was a well-kept secret that Sears had developed a truly beautiful E-commerce front end to their business. The problem was that the backend was a mess of arcane systems and processes, and the business leadership was clearly not interested in organizing around consumers’ new shopping behaviors. We all know how that ended.

A second issue that retailers should heed is that information and technology really are the change enablers in these times – digital transformation is a real thing, and the new age of retailing isn’t merely a bolt-on to the old one. Retailers tell us that they want to use new cloud-based services and APIs to extend the life of their legacy systems with modern front-ends. That’s extremely risky – just ask Debenhams (or the Sears E-commerce team)!

At the same time, embracing the “new” is dependent on maintaining the cultural knowledge of the company’s legacy. In their initial optimism about a digital transformation, Debenhams jettisoned the cultural knowledge embodied by the people who supported the old processes and technologies. I’m reminded of the old bit of wisdom, “if you don’t know where you’ve been, you won’t know where you’re going”. Keepers of the status quo might be a royal pain, potentially irritating “nattering nabobs of negativism” (thank you, Sprio Agnew!), but they are worth keeping on board because they can tell the new team how the company got to where it is and how to avoid making the same mistakes all over again.

Finally, the need for agility is real – and companies should look at everything they’ve got and determine if those things facilitate change or are boat anchors. Debenhams was drowning in debt, but the company kept piling on – a formula for disaster. For some companies it’s the real estate holdings or 33-year leases, while for others it’s their product lines. Very few companies have the courage to do what (for example) IBM has done over the last few years by jettisoning product lines that aren’t part of its future plans. Agilty is the plan – or it should be!

Maybe Debenhams will live on to fight another day – for sentimental reasons I hope so. I miss some of the great old brands that defined the “good old days” of retail – those days were fun! But we live in a different world now, and while it might be pleasant to think about how relatively “nice” the old world was, the new one is full of extraordinary challenges and opportunities.