The China Trade

The status of trade and financial relationships between the U.S. and China are sure to get some people in the U.S. riled up about domestic jobs, taxes, debt, and general economic well-being. That kind of rhetoric got kicked to a high rev level during the Great Recession, as unemployment rates in the States exceeded 9%. But despite that kind of sentiment, American shoppers are addicted to affordable fashion, and that drives a lot of the business between the two trade giants. An apparel industry report issued by The American Apparel & Footwear Association (AAFA) entitled ApparelStats 2012 noted that, “on average, every American, including every man, woman, and child in the United States spent $910 on more than 62 garments in 2011. ” Do the math: that’s an average of less than $15 per item.

While U.S. domestic manufacturing has shown some new signs of life, the business today is overwhelmingly an “international ” value chain. Kevin M. Burke, president/CEO at AAFA stated in November 20912 that, “In 2011, domestic apparel manufacturing grew 11.1% and, for the first time ever, domestic production’s share of the U.S. market grew, driving import penetration in the U.S. apparel market below 98%…. ” (emphasis added). China imports represent about one-third of that 98%.

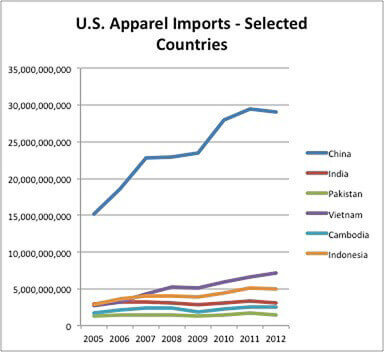

There’s also a fair amount of loose talk about companies finding even lower cost suppliers in other countries, but recent U.S. Dept. of Commerce data highlights China’s overwhelming volume advantage (chart).

The relationship between U.S. retailers and Chinese manufacturers is a case-study about the nature of the global economy. But as with all business arrangements, sooner or later it gets down to personal relationships, and so I thought it would be a good idea to get that personal perspective from someone who actually is directly involved. To that end, I interviewed Meegan Robinette, who is an agent representing two Chinese manufacturers, Shanghai Shengda and Weihai Luda. “We do accessories, such as scarves, ‘cold weather’ – which includes hats, gloves, mittens, belts, ‘home’ – which includes throws and blankets and bags, ” explains the trader. “Target US is a big account, and we have accounts like Gap, Banana Republic, Old Navy, Nordstrom, and Federated, as well as Pottery Barn, Restoration Hardware, Williams-Sonoma. You name the company, and the odds are they are doing business with one of my factories, even if it’s only seasonal. “

The Nature of the Relationship – From the Factories’ (And Agent’s) POV

Ironically, Meegan’s business is strong because of the recession. “A few years ago, the factories really got hurt, ” she explains. “When business declined, all the small factories in China went out of business. It was odd – I had started doing this seven years ago, but my business actually grew and my factories grew, and we are doing much better than 10 years ago. “

The agent continues, “what the Chinese found valuable in me is that I had been a Target employee in the AMC days – which at the time did all the sourcing for Target, Mervyns, Marshall Fields, and Bloomingdales. I worked in the Mervyns headquarters, on a separate floor. But when Mervyns was sold, I left on the same day because I knew their days were numbered – they didn’t have the buying power of Target behind them anymore. Soon I was recruited by a domestic importer (DI) – they are manufacturers in the United States that do all of their manufacturing in China or India or wherever, but the design teams are domestic – and they present products to the retailers that way. But Shanghai Shengda, one of the factories I’d introduced to the DI, called me and said, ‘I don’t want to work with your DI anymore, I want to go direct.’ This was illuminating to me – I had been with Target for so long, and we used agencies in Hong Kong and India via Target sourcing – it was all cut’n’dry. But you really don’t need a middleman. Going direct is more profitable for the manufacturer and more profitable for the retailer. “

But it isn’t as easy is simply cutting out unnecessary middlemen, says Meegan. “The factories still need someone to guide the product – that’s where they fall apart, especially in China. They just don’t have a sensibility about products in the Western market. You have to remember that 15 or 20 years ago in China, everyone wore black! So the creative part was a good niche for me. Since I have friendships both at retailers and in China, I thought I’d give it a shot. And what the factories found valuable in me is those relationships. They still work that way in China- it’s all about relationships and who you know, and ‚’bragging rights’. It was prestigious for a smallish factory to be able to say that they had an American former senior product manager from Target working with them. “

The Nature of the Relationship – From the Retailer’s POV

Back in April 2010, RSR published a report entitled Getting It Right The First Time: Designing And Delivering Merchandise That Sells. In the report we wrote, “… the time has come for retailers to embrace Product Lifecycle Management … we recommend working the “virtuous cycle ” of supplier relationship management. “

Inherent in that statement is a point-of-view that on the retailer side at least, modern Internet-enabled inter-corporate technologies are important to enable global trade management. And while that may be true once a P.O. is cut (at least for the larger companies), what happens up to that point is probably driven the old-fashioned way for retailers too.

Meegan described one retailer relationship this way: “my old boss and friend was a divisional merchant at <retailer X>. The buyers and the divisional would select everything and confirm the program- I’d actually have the P.O., but then they would have to ‘sell’ the program to the owner. And if she didn’t approve it, even though the P.O.’s had been generated, they’d call and cancel. It’s hard to do business that way, because there’s so much control at the top. So, the good people leave to work at other places. Any now my friend is a merchant at <retailer Y>, and that’s why I’m doing business there, even though they don’t have the number of stores needed to drive the kinds of volume that’s best for my factories. “

There are several little “truths ” implied in her story: first, people work with people – not companies; second, the “merchant prince ” still reigns in many places; and third, friends will help out friends for reasons beyond pure dollars-and-cents. In other words, it’s a trust relationship, just like the old days, at least at that point in an order transaction.

The Process

Meegan finds similarities as well as differences between American companies and their Chinese partners. “Of course, there are language and cultural barriers, ” explained the factory rep. “The way the Chinese might present product is to lay it all out in no particular order and mismatched, and say, ‘have a look.’ I make sure that the products are presented as collections. But like American companies, the Chinese are good at finding the most direct path to the desired result. “

Nowadays, retailers want the factory agent to come to them and show them something new – they’re budgets are smaller and they don’t travel as much as they used to. “Buyers used to go to Europe six times a year, ” says Meegan. “Now, not so much. Europe isn’t doing well -there’s not the creativity that used to be there. What my retailer designers want me to do is – probably twice a year – do a big presentation for a season. They’ll choose a lot of the samples, and as each delivery approaches, they’ either order from the samples exactly as they are, or they’ll tweak them a bit. Or sometimes, they’ll get a sample from other retailers and make it their own – and order it from us with a different yarn or weave or stitch, or whatever. “

With retailer design team cutbacks in recent years, more of the creative process has fallen to the agent. “I do my research – I look at the market, read every magazine known to mankind (I read them on the airplane on trips back and forth to Hong Kong and Shanghai), and nowadays spend 4 or 5 hours a day checking out retailers that I think are benchmarks for my accounts. I send inspirational pictures to the teams. Although we might not make a particular design, my factory may have a joint venture going with another factory. I have to make sure that they are compliant with my retailer’s standards, but then we can offer the design. “

So what about the notion of a design document being sent out to bid, as you would see in a discreet manufacturing value chain? “You used to see that a lot more, ” says Meegan, “but you have to remember that retailers have really downsized – they have skeleton design crews today. Where I used to have 10 designers to work with, now I might have 3. Retailers are looking to me for inspiration, because it makes their job a lot easier. Sometimes that means taking boxes of samples to the retailer, opening them up, laying them out in some kind of an order, and helping them choose. “

While inter-corporate technology may not have much to do with the interaction, “process ” certainly does. According to the agent, whether a retailer uses agents or goes direct, it’s important to have a timeline or “roadmap ” – a time & action calendar. These documents are very detailed, and integrated between the retailer, manufacturer, and the design time so that everyone is on the same page. The roadmap, which according to Meegan started to be used throughout the industry about 10 years ago, is generated by the retailer with the help of the agent. According to the factory rep, “You get these seasonally – Old Navy for example does one for each quarter. Target bases everything on ‘in store date’, while Old Navy bases it on ‘in warehouse’ date. Manufacturers prefer the ‘warehouse date’ because they have no control over what happens between the retailer’s DC and the stores. Manufacturers’ responsibility is to get it to the U.S. based freight forwarder on the date specified. “

The big ‘no-no’? Big cancellations after the order is in-process. According to the factory rep, many agents will not work with certain retailers because, “if they didn’t do a good job of analyzing what their needs were going to be, they expect the factories to eat it. Factories have all the liability as it is. They work a year out, buying all those yarns before seeing a P.O., and the raw materials suppliers don’t work off of P.O.’s – it’s ‘cash and carry’. And factories have to lock up their production schedules in anticipation of a big order – that means that they have to say ‚’no’ to someone else. ” So when a big order is cancelled late in the process, the manufacturer loses more than just the order – they may lose the season.

Moving On?

While there’s talk in the popular press about rising labor costs in China and manufacturers looking for new sources of cheap labor, the agent isn’t seeing any wholesale move in that direction. “First of all, most large U.S. companies won’t even let their product managers travel to places like Cambodia, ” says Meegan. “Even India and parts of China can be intimidating. The transformation in Shanghai in the last two years has been remarkable. It’s very westerner-friendly. A lot of people are looking at Vietnam, but that business seems to be coming from Korea and Taiwan, where labor costs are high. China is a big country – there’s still a lot of low cost labor available. “

So, China is still the big player – and it’s likely to remain that way for the foreseeable future. While other AsiaPac countries have infrastructural problems (for example, unreliable transportation systems), China has made huge investments. While Central and South America have few tariffs, factories there have a history of unreliability. India will likely continue to be China’s biggest competitor for business, but according to the agent, “you have to expect orders to be late “, whereas the Chinese manufacturers have a good on-time record.

But according to Meegan, the other factor is that “Americans are creative – ‘rich cowboys’. The Chinese live such structured lives – doing business with Americans is appealing – they enjoy the energy of American retailers. “