Stores: It’s Time To Address The New Economics Of The Box

The RSR partners have talked and written a lot over the years about the “economics of the box” – basically, how stores can make money. The first mention on our website came in a 2015 newsletter article that stated: “mature retailers in mature markets will not be able to drive enough growth to satisfy investors purely by opening new stores. And that moment may be on us sooner than we think. When that moment comes, the question retailers will have to ask themselves is ‘How do I drive more growth out of my existing stores?’”

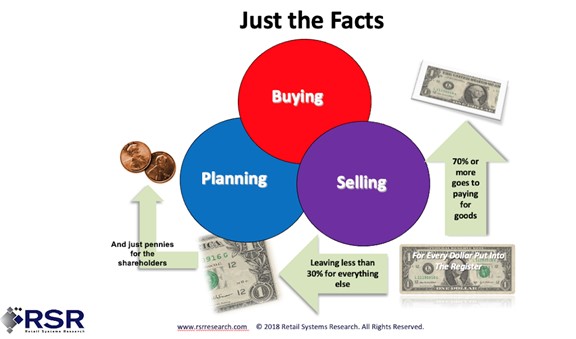

When we conduct sales training sessions for technology salespeople, we always walk the attendees through a sample profit & loss statement, to demonstrate just how little it takes to make a profitable store an unprofitable one, and vise versa. We always start the discussion with this simple illustration:

Invariably, the attendees that are new to retail are stunned on just how hard it is to make money by operating a store, especially when it comes to those merchants who sell consumer products and fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) merchandise.

This became an important part of a discussion I had last week with a reporter from the San Francisco Chronicle, Carolyn Said, who wanted to explore drugstore operator Walgreens’ decision to close five stores in San Francisco (What Walgreens Isn’t Saying: Store Closures Show A Strategic Shift To Survive In The Age Of Amazon, SF Chronicle, 10/23/21) .

The popular reason for this move– and the one that Walgreens is promoting – is that “it’s all the fault of a liberal city giving free rein to lawbreakers”, i.e., that shrink from shoplifting is destroying the profitability of those locations. But the SF Police Department is calling “BS” to that rationale; another Chronicle article reported that, “Data released by the San Francisco Police Department does not support the explanation announced by Walgreens that it is closing five stores because of organized, rampant retail theft. … the five stores slated to close had fewer than two recorded shoplifting incidents a month on average since 2018.”

I pointed out to Carolyn that what isn’t being discussed are the possible additional costs Walgreens is incurring to discourage theft. For example, the company employs off-duty SF policemen in the City to put a law enforcement presence in the stores. That decision alone could tip to the expense ratio of those stores in the wrong direction. To paraphrase something my boss was fond of saying, how many tubes of toothpaste does the store have to sell to pay for that?

Walgreens is a classic FMCG company, and like other retailers in that vertical, the company has been militant in its efforts to keep a tight lid on “variable expenses” – the biggest component being the cost of labor. Strict cost control is most evident when a consumer goes to a store to get a prescription filled; to be a Walgreens customer is to be familiar with pharmacy staff lunch hours, because the company literally shutters the department every day to give the staff a lunch break instead of paying to have sufficient staff on hand to service customers. So it’s not hard to see how easily hiring off-duty cops could be one burden too many for some stores.

But let’s get real: there are probably more, and more complex reasons why the retailer is closing 10% of its SF stores, and those reasons are affecting all retailers, so let’s list them:

(1) Retail in America is over-stored. Remember the “retail apocalypse”? That was a popular meme in 2017, when retailers were panicking about Amazon’s seemingly unhindered ability to pull sales away from retailers. By 2019, RSR research showed that retailers had come back to believing that stores have a future, but only if they are redesigned to be differentiating by virtue of the experiences that they create for consumers.

Walgreens knows this! In fact, the company has a new-concept design that offers high-quality value adding health services. CVS is doing the same thing. But – America is still overstored, and that has only become a bigger issue as a growing percentage of sales are now shipped directly to consumers.

(2) Consumers want more and better service in the store, especially when they’ve gone to all the trouble of starting their shopping journeys online. This is the essence of omnichannel retailing – but it does mean more tasks in the store and that means more labor.

(3) Consumer omnichannel shopping results in more investment in store technologies. To cover the additional costs associated with omnichannel order fulfillment, retailers must automate non-selling functions to the extent possible. RSR friend Greg Buzek of IHL Services put it succinctly last week during a panel discussion entitled The Future Of Commerce, hosted by the University of Southern California: “automate everything you can”.

(4) Finally, there’s the elephant in the room: employees are sick and tired of being compensated poorly. RSR partner Paula Rosenblum speaks to this issue in a companion article to this one.

I’m not here to defend San Francisco or condemn Walgreens. The retail industry as a whole has a big challenge on its hands, and that is that the economics of the box don’t work very well anymore. It’s not an easy challenge to address because it challenges retailers’ traditional operating model – but the industry has to stop dancing around it.

20th Century retailing just doesn’t work as we get into the 3rd decade of the 21st. It’s time for retailers to address the new economics of the box.