Running Downhill Too Fast: US vs. UK

In last week’s Retail Paradox Weekly, my RSR partner and co-author of our most recent benchmark report on the state of pricing practices in retail identified a “Pricing Paradox “. Here’s what Paula Rosenblum wrote:

“Retailers acknowledge, across this and several other benchmarks, the need to create a consistent customer experience across channels. Retail Winners in particular are fixated on this notion… Yet we also see a trend, particularly among those same Retail Winners, to focus on channel specific promotions…Three times as many Retail Winners than laggards are executing on these channel-specific promotions. “

But the report itself focuses on another (just as startling) paradox. Simply put, we found that although retailers claim that the primary objective of their pricing strategies is to maximize gross margins, at the same time they have increased the number of promotions in their attempts to buy some loyalty from ever fickle and demanding consumers.

Faint Praise

In the study we learned that 55% of our retailer respondents have increased their promotional activity (and 21% said “increased significantly “). At the same time, 62% of those retailers said that their pricing strategies were only “somewhat effective ” in driving bottom line results, compared to 27% who said that they were “very effective “. This is what my Irish grandmother used to call “being damned by faint praise “.

And so Paula and I looked inside the numbers to see if we could get a better understanding of the paradox that even though retailers say they are trying to improve their gross margins, they in fact are giving them away in the form of promotions and markdowns.

It’s Mostly a US Thing

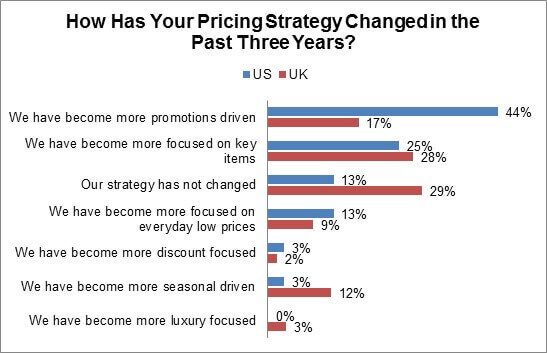

In our last two years’ benchmarks on pricing, we have seen that the retail industry has been in the grips of what can only be called promotional fever. In the new study, we had a particularly interesting opportunity – to contrast pricing practices between the United States and another country, the United Kingdom. Our retail respondents report that while the number of price changes continues to rise everywhere, promotional activities are far more prevalent in the United States (figure).

While it seems that UK retailers watch competitors’ prices just as keenly as US retailers do, the focus is more about being fair than being hot when it comes to pricing. In fact, US retailers differ from the overall response group significantly when it comes to identifying the top business objective: American companies feel that “convey(ing) the value proposition ” is #1 (58%, compared to only 29% of British practitioners). Based on how US retailers responded to the benchmark survey, it’s hard not to conclude that for many practitioners, “value ” equals “price “. But whether it’s called the Amazon effect or the Walmart effect, it cannot go on forever. Just ask Family Dollar, who last week announced that it will close 370 stores and open fewer new ones. On April 15th, The Christian Science Monitor conjectured:

“By the looks of things, Family Dollar – a mainstay American dollar store franchise – has been doing bangup business: From rural Rutledge, Ga., to high-end neighborhoods here in the Atlanta metro area, newly built storefronts have been opening in rapid succession. It’s that expansion that made the news that Family Dollar is now suddenly retrenching by closing 370 stores so surprising. The announcement illuminates, at least to some economic analysts, the changing attitudes of the American consumer and how that impacts the big money behind cheap deodorant and chips… (it) may suggest a rumble of change in the American economy. After a half-decade of economic headwinds, Americans are, bit by bit, feeling richer as household worth has hit 5.1 percent annual growth. “

I told a story from my past in another Retail Paradox Weekly column not long ago that my old CEO (Bob Long of Longs Drugstores, who sadly passed away just last month) once remarked that “having the lowest price strategy just means you don’t have a sustainable strategy “. He went on to explain that any retailer on any day can beat you on price if they are willing to take the hit. It appears from our study that there are a lot of retailers in the US still willing to “take the hit “.

Inconsistencies ‘R’ Us

Whether it supports “maximizing gross margins ” or not, the data shows that US retailers are more promotionally driven than UK’ers. So the next question might be, “how well are you doing at it? ” The answer: not so well, apparently. Either as a driver or as a result of their heavy promotional activities, US retailers are more concerned than their UK counterparts about the increased price sensitivity of consumers (58% compared to 53%), and much less confident that they are effective across all selling channels (only 39% say that they are confident that they “have effective policies in place to manage different prices and promotions across channels and touch points “, compared to 57% of UK retailers).

There’s more: 76% more US retailers than UK ones express that they are operationally challenged to “forecast the impact of potential pricing decisions “, and 50% more American companies than British operators admit that they struggle to measure the impact of executed pricing decisions “. And while about 28% more US retailers than their UK counterparts feel that competitor price data is “very important “, the most favored way for US retailers to collect that data is “manually ” (a stunning 45%).

The ‘Running Downhill’ Analogy

All of this reminds me of something we’re all supposed to learn as kids: don’t run downhill. (With apologies to professional runners who have techniques to avoid this) kids learn very quickly that if the hill is too steep and those legs get pumping too fast, pretty soon you’re going to get ahead of yourself, lose control, fall down, and get hurt. The problem is, once you’ve started, how do you stop? US retailers in particular are running down a steep hill to nowhere too fast.

For me at least the answer has to be, “define a value strategy that is based on something besides red-hot prices. ” That doesn’t mean that “price ” shouldn’t be an important variable in the value equation. But it can’t be the only one. Remember what my mentor Mr. Long said: “having the lowest price strategy just means you don’t have a sustainable strategy “. Nowadays, it seems that UK retailers have a better handle on that than their US counterparts. Whatever the underlying sociological and economic reasons, there’s something to be learned from it.