Manhattan Momentum 2018: Making Omni Profitable

Since consumers made “digital ” such an important part of their shopping journeys a more than a decade ago, the primary focus for retailers has been on creating digital shopping options for the consumer, and integrating those options into mainline business processes. Retailers have experimented with add-on capabilities to build sales and (hopefully) loyalty, and chief among these add-ons is an array of fulfillment options.

But there are early indicators that retailers are beginning to weed out options that are not profitable. The most notable example in the news was the announcement that canary-in-a-coal-mine UK retailer Tesco is shutting down its Tesco Direct non-food operations this month – and the retailer cited the high cost of fulfillment and high advertising costs as the reason. Tesco’s struggles over the past decade seem to presage general industry trends; for example, in 2017, the company decided to charge customers a fulfillment fee for Click & Collect orders. That was the first public admission by a big retailer that the costs associated with Click & Collect (or as it is called in the U.S., “BOPIS ” – buy-online-pickup instore) were killing the per-order profitability of those customer orders.

Nonetheless, when the dust settles, the combination of BOPIS and direct-to-consumer fulfillment from a centralized DC will probably end up being the customer order fulfillment strategy favored by most retailers. Fulfillment from the DC makes obvious good sense: eaches pick-and-pack automation and shared inventory pools with the traditional store fulfillment processes should drive down costs. The reason BOPIS will ultimately succeed is because of two things. First, stores are the network of forward positioned inventory locations, closest to the customers (unless of course their sites were badly selected in the first place, but that’s the topic of another blog someday). Secondly, the store represents a point of cost aggregation. Although costs associated with BOPIS are bedeviling retailers now, those costs can be systematically driven down with the right investments in technology.

Manhattan’s ‘Push Possible’ Message

Manhattan Associates held its Momentum 2018 conference in Florida late last month, and rolled out its new message, “push possible “. That’s a double entendre of sorts; Manhattan wants to help retailers become more agile with a supply network that is inherently “push/pull “. N:N network designs are different – and more complex – than the legacy “push ” oriented 1:N designs of the last 60 years. What Manhattan wants to do it to help propel retailers forward in the context of Omnichannel retailing by helping them optimize complex N:N supply networks.

Manhattan has two of the ingredients essential to enabling a profitable Omnichannel retail business: an industry leading distributed order management system, and a widely implemented supply chain portfolio. Retailers are recognizing that, (1) an Omnichannel order management capability is the centerpiece of new enterprise-wide selling systems (just as POS was in the last generation), and (2) the DC/warehouse has a new and important role in supporting both direct-to-consumer and BOPIS. Both of these capabilities require big investments in software, but Manhattan’s leadership is aware that old channel-specific solutions aren’t going to be enough. And so at the conference, the company’s leadership made a point of highlighting how the company is making big new investments in the portfolio to be omni-aware.

For example, CEO Eddie Capel highlighted the Manhattan Active Supply Chain, which includes new capabilities to enable “waveless order streaming ” for customer order fulfillment, management for common pools of inventory to support more traditional “wave ” picking in addition to the “waveless ” kind, and shared warehouse automation. Capel also shared what he called “omni-aware inventory optimization “, the ability to optimize inventory across multi-echelon supply chain networks. These improvements to the solution portfolio all have to do with managing the chaos that can ensue when a point of customer demand (for example, an order from eCommerce), and the point of order fulfillment (a fulfillment center or a store) may not be in the same place.

Manhattan is also addressing its demand forecasting & replenishment capabilities. Like some of its competitors, Manhattan is leveraging “big data ” analytics to add context to new information, like the weather, that can shape demand, and new AI algorithms are being integrated into the solution to help retailers better understand the impact of promotions in shaping demand. All of this is part of the greater effort to optimize inventory across the enterprise.

When it comes to the order management system, Manhattan has made improvements to make it “Omni-aware “, adding an “Omni-cart ” – essentially a shopping cart that can be built in several channels, eg. started in the eComm channel, added to via a call center interaction, and completed in a store. The point of this change is to enable a single view of the customer interaction from any touchpoint.

Moving It To The Cloud

Manhattan CTO Sanjeev Siotia spoke to Manhattan’s efforts to put all of these new capabilities into the cloud. Of course, the company isn’t the first one to do this, but Sanjeev posed the cloud imperative in a practical way with the question, “is cloud inevitable? Why? ” Sanjeev laid out four important values that cloud brings to the table: “improving the speed to value of implementations from 5 years to 4 months “, “breaking a large rock <monolithic solutions> into little pebbles to make them easier to move “, “upgradable extensibility “, and “zero downtime upgrades “.

I’ve been hearing similar promises for nearly twenty years, ever since the advent of object oriented programming in the 1990’s, and (a little later) services oriented architectures. Interestingly, it was Sanjeev’s team at Yantra – a software company that was way before its time, that first pointed the way. The latest iteration of this concept is “micro-services “, and what that means to the layman is that solutions are built as a set of capabilities that are “net native ” (think of Salesforce). The concept is becoming mainstream (for example, I recently commented on Aptos’ move in the same direction). In Manhattans’ case, the company is making several important-to-your-IT-team commitments: the extensive use of open-source middleware, auto-scaling (adding or subtracting computer resources on-demand, to escape from the necessity of over-configuring the technical environment to handle the worst-case scenario), automated testing, and containerization (virtualization of the operating environment). While a retailer’s Chief Merchant may not understand- or even care – about these things, the CIO definitely will.

Do Retailers Really Need All Of This?

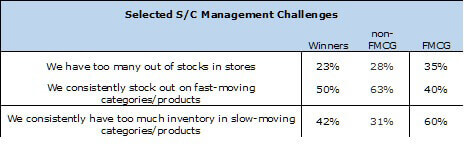

Taking a cue from Sanjeev Siotia’s presentation, one might ask, is all of this software innovation really necessary? Or is the technology community (once again) way out in front of its skis? I’ll answer that question with a single bit of data that RSR culled from a recent survey. We asked a simple question, “Is your supply chain helping or hurting your company’s performance? ” This is what we learned:

Clearly, there’s huge room for improvement particularly among average and under-performing retailers. And as Omnichannel selling continues to gain traction with consumers, those retailers who don’t figure out how to make a profit in a world where demand and fulfillment can be triggered anywhere throughout the enterprise, will be left behind.

Manhattan wants to push forward the possibilities to those retailers to help them to be the next generation of Winners. Good for Manhattan, and good for the retail industry.